By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

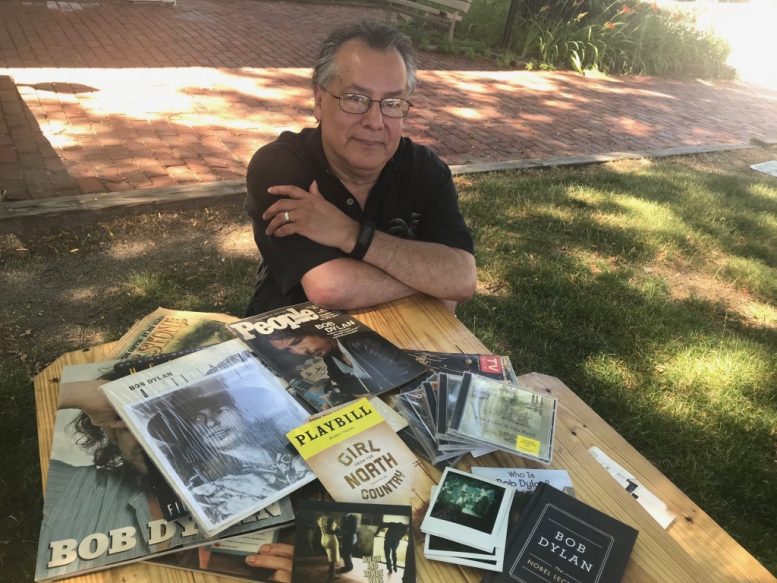

Alberto Gonzalez discovered a lot in 1973 when he came to Bowling Green State University from rural Fremont where he grew up.

Bob Dylan was one of those discoveries.

He had to do a short project in his TV production class.

He didn’t know much about Dylan beyond what he’d heard on the radio, but decided the folk troubadour would be his subject. He trekked downtown to Finders Records and bought several albums for visuals, though he’s not sure any of the music was played on the show.

He also needed someone to deliver the script he wrote, so he turned to a fellow student whom he’d met the semester before in a theater class, someone he was just getting to know.

JoBeth Enders said yes.

Gonzalez brought the Dylan records home and listened to them. He was impressed by the insight of songs, “Pawn in their Game,” as far back as 1963, tackled the issue of whiteness as a privilege as well as addressing “the pressures of it where people have to act a certain way because they’re White and if they don’t (act that way), they’re traitors.”

And there’s Latin influence that finds its way into some songs. He appreciates “the fact that Brown people as well as African Americans were on his radar screen.”

Gonzalez also connected with a certain Midwest sensibility. Though Dylan liked to present himself as a hipster from New York, he was still a guy from Minnesota. Those Midwest elements are “ something I can connect to. To hear that in some of those songs was something that was reassuring to me.”

Gonzalez, who is Mexican-American, said: “I think of myself as a Midwesterner. I think about that because most people assume I’m from Texas or from southern California, but I’m from Fremont, Ohio. “

A few years later when he was pursuing a doctorate in communications at Ohio State he collaborated with one of his professors John J. Makay to publish his first academic paper, “Rhetorical ascription and the gospel according to Dylan” in the Quarterly Journal of Speech, a top journal in the field.

Now as Gonzalez, a Distinguished Professor in communications BGSU, contemplates wrapping up his academic career, he’s turning his attention back to Dylan. He’s thinking that “before I hang everything up to get a bunch of people together writing essays on Dylan.”

That’s “percolating” but Gonzalez, who has taught at BGSU since 1992, has other projects to complete. The focus of his scholarship now is the rhetoric of reunification in South Korea.

Still returning to Dylan would be a way to round out his career.

He’s hoping he may have completed by 2023. His wife, who has joined him for the interview, is a bit skeptical about that timeline. How much more will Dylan produce, JoBeth (Enders) Gonzalez wonders.

A number of writers have noted that Dylan himself, now 79, is in an elegiac mood in his recently released “Rough, and Rowdy Days,” the 39th studio album of his career, and the first since 2012 to feature original material.

Many of the “Rough and Rowdy” songs deal “with finality and frailty,” Gonzalez said.

He is glad to see Dylan move beyond “his crooner stage,” during which he covered the American songbook sung by Frank Sinatra. Gonzalez said the repertoire didn’t work any better live than it did it did on the three albums of the material Dylan released.

Gonzalez is fascinated that though the style of songs changed, Dylan still uses the same band he’s employed for years. It’s an ensemble that allows Dylan to range through an eclectic range of styles, all shades of the blues, early jazz, folk, and country. “He and his band is put together to make a really distinctive sound.”

The new recording is in keeping with how Dylan approaches songwriting. “He throws up these lyrical word clouds to see what’s going to stick, what’s going to resonate.”

And those lyrics have plenty of echoes both of his own work and the American musical tradition.

Two country stars, Jimmie Rodgers and Waylon Jennings, recorded songs with similar titles, and wordplay like “Your days are numbered so are mine” reminds Gonzalez of earlier albums.

Gonzalez knows the Dylan canon. He’s been to more than 40 shows, dating back to when he and JoBeth saw him perform in 1978 at the University of Toledo. He even got a chance to see the musical “Girl from the North Country” in previews earlier this year right before Broadway went dark. The musical sets an original story to Dylan songs.

Gonzalez brings to his work on Dylan a musical sensibility. He started playing guitar when he was in college. While those early guitars were hard to play, it allowed him to bring an awareness of the harmonies to his analysis.

For a number of years, he teamed with local musicians Tom Gorman and Matt Webb in the Traveling Chillberries, a play on the Traveling Wilburys, a super group Dylan was a member of in the late 1980s.

And Gonzalez performed the song “Make You Feel My Love” with his daughter Monica at a wedding.

Monica and her sister Veronica were introduced the bard of Hibbing, Minnesota, early on. They would march around the house playing harmonica to “Like a Rolling Stone.” Their father told them: “This is the best rock ‘n’ roll song ever. I drilled that into them.”

He even took them to concerts, though it took them until they were older to come to appreciate songwriter.

Gonzalez has seen Dylan all over the country, and with various collaborators – Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, the Grateful Dead, Mavis Staples, Paul Simon, Carlos Santana and others.

He heard him when guitarist G.E. Smith was in his band. He later got to talk to Smith when the guitarist performed at the Black Swamp Arts Festival in 2001.

That’s, he said, the closest he’ll get to actually speaking to Dylan himself, and that’s all right with Gonzalez. When people ask him if he’d like to interview the legend he responds: “No, I think he’s a probably a weird guy, nobody I would relate to as a person.”

With “Rough and Rowdy Ways,” “He’s reminding us that he’s still around. I think the timing is good. It’s almost like a voice of continuity. He’s letting us know there’s this sense of social conscience.”

On the 16-minute song “Murder Most Foul” about the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Dylan explores another American trauma at a time when the pandemic has caught people off guard.

The song is packed with cultural references, including name checking dozens of musicians.

“He’s not really singing, just talking way through the song,” Gonzalez said. “We’re undergoing trauma now on a number of fronts.”

And there’s something reassuring about having Dylan’s familiar voice back in the cultural mix.